Liz Lerman has just returned from a jaunt to Ireland and England where she led workshops on Critical Response and other methods. At the Abbey Theatre studios, through the cooperation of Create, she taught and facilitated a CRP session with Irish choreographer Ríonach Ní Néill. Rionach presented her work Seandálaíocht (Archaeology), which she describes as “a highly personal exploration of the paradox of a language only spoken by one person.”

Rionach reflected on her experience with CRP in a message she sent to Liz and some of the workshop sponsors, and graciously granted permission for me to excerpt it here. I especially appreciate hearing her “next steps” and her reflections on the implications of Critical Response in an Irish cultural context. Thank you, Rionach.

“It was a privilege to me to present my work for the critical response workshop. I knew that, concerning identity and the Irish language, it dealt with a very sensitive issue in the Irish psyche and that everyone would have an opinion and an emotional response to it…. The workshop gave us the tools to engage with each other and the work, the method providing a safe place for the audience to give, and me to receive, feedback, and yet for us to be as honest and direct with our opinions as we needed. It was such an enriching experience for me. I have so much information to process and perspectives with which to revisit the work with further clarity and depth. I will be viewing the work as starting from the programme note. I will be examining how, without compromising its and my truth, it can communicate more precisely across a language barrier. And I will be enjoying performing it, as I now realise that it can say what I want to convey.

“I think the method is of particular use to us in Ireland, a point that arose in the workshop. Although words and the Irish are intrinsically linked, I think our love of the beauty of the sounds, the verbal landscapes and dances we can create with words, sometimes obscure the meanings. We use language to delight, to amuse, to dazzle, but maybe not so well to communicate. And so we are not so good at criticism, in fact, criticism here is usually equated with negativity. The method, in its polite neutrality, made us take responsibility for our thoughts, and made us focus on what we were really saying and really hearing. Common sense maybe, but a very profound sense.”

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Friday, December 5, 2008

Notable Quotable: Woody Allen

This master of mordent humor might be answering the question: How do you measure success?

If you're not failing every now and again, it's a sign you're not doing anything very innovative.

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

The Lens of Love

Yesterday I was in Manhattan working with fabulous colleagues from Liz Lerman Dance Exchange and Facing History and Ourselves. Our two organizations co-facilitated a workshop for New York City-area school teachers.*

As with many Dance Exchange workshops, this one culminated with teams of participants showing short text-and-movement studies that they had created using tools and content shared in the day’s activities. Fabulous colleague Elizabeth Johnson (Associate Artistic Director of Dance Exchange, seen at far right in the above picture) facilitated the presentation of these Build-a-Phrase dances. In her introduction she said something like this:

You’ve worked quickly. None of us have had enough time. When you do this with your students, they will not have enough time. So, as we watch I’d ask you to keep in mind the idea of work-in-progress. I’d like you to look through the lens of love and set aside judgment for the time being. After each showing we’ll talk about what we saw, so be thinking about what is meaningful, surprising or memorable about what you are watching, or what you might want to take away.

As I listened and watched, it occurred to me that here was another answer to the question “Can you just take parts of CRP or do you have to do the whole Process every time?” For in moments like this, we often employ a modified Step One as the primary means of reflecting on the choreographic quick-studies that people have produced. It affords a shortcut to insights and learnings that both makers and watchers have gained in the course of their shared experience.

“The lens of love” is a phrase I’ve heard Elizabeth use before. Later she reminded me that it was former company member Marvin Webb who was the first to use it at the Dance Exchange. These words struck me afresh as being just right for the moment we were in. While I wouldn’t recommend it for use during a formal CRP, I think it’s a great fit near the close of a day in which a group of people, primarily new to each other, have made themselves vulnerable, stretched their comfort zones, and built community. Its affirmational spirit is balanced by the rigor of the questions that accompany it. And it names the moment nicely, because when you’ve got a room full of teachers as committed as this group, you’ve got a room full of stong, active, no-nonsense love.

________________

*This workshop was part of an ongoing program in which we’re combining aspects of Dance Exchange’s Small Dances About Big Ideas with Facing History’s Choosing to Participate curriculum. It offered methods for applying movement and artmaking techniques to teach about active citizenship and standing up in the face of injustice. Dance Exchange’s work with Facing History is supported by grants from the Covenant Foundation, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, and the Maxine Greene Foundation.

As with many Dance Exchange workshops, this one culminated with teams of participants showing short text-and-movement studies that they had created using tools and content shared in the day’s activities. Fabulous colleague Elizabeth Johnson (Associate Artistic Director of Dance Exchange, seen at far right in the above picture) facilitated the presentation of these Build-a-Phrase dances. In her introduction she said something like this:

You’ve worked quickly. None of us have had enough time. When you do this with your students, they will not have enough time. So, as we watch I’d ask you to keep in mind the idea of work-in-progress. I’d like you to look through the lens of love and set aside judgment for the time being. After each showing we’ll talk about what we saw, so be thinking about what is meaningful, surprising or memorable about what you are watching, or what you might want to take away.

As I listened and watched, it occurred to me that here was another answer to the question “Can you just take parts of CRP or do you have to do the whole Process every time?” For in moments like this, we often employ a modified Step One as the primary means of reflecting on the choreographic quick-studies that people have produced. It affords a shortcut to insights and learnings that both makers and watchers have gained in the course of their shared experience.

“The lens of love” is a phrase I’ve heard Elizabeth use before. Later she reminded me that it was former company member Marvin Webb who was the first to use it at the Dance Exchange. These words struck me afresh as being just right for the moment we were in. While I wouldn’t recommend it for use during a formal CRP, I think it’s a great fit near the close of a day in which a group of people, primarily new to each other, have made themselves vulnerable, stretched their comfort zones, and built community. Its affirmational spirit is balanced by the rigor of the questions that accompany it. And it names the moment nicely, because when you’ve got a room full of teachers as committed as this group, you’ve got a room full of stong, active, no-nonsense love.

________________

*This workshop was part of an ongoing program in which we’re combining aspects of Dance Exchange’s Small Dances About Big Ideas with Facing History’s Choosing to Participate curriculum. It offered methods for applying movement and artmaking techniques to teach about active citizenship and standing up in the face of injustice. Dance Exchange’s work with Facing History is supported by grants from the Covenant Foundation, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, and the Maxine Greene Foundation.

Monday, November 24, 2008

Build Feedback and They Will Come

On Saturday, as part of FotoWeek DC, I was at my photography home-base, Photoworks Glen Echo, taking part in a digital portfolio review session. Photographers, both fledglings and veterans, had the opportunity to show a selection of images that they brought in on discs or flash drives to be projected on the wall. I was invited to be one of the reviewers, a new experience for me. Here, in no particular order, are a few observations from that experience:

1. People really want the feedback experience. We had high participation in this event, much of it from folks who'd never been to Photoworks before. It seems that if you just hang out the shingle and say you are offering critique, folks will show up. Why? Some of it is a desire for guidance, since most of the photographers were asking for advice about organization or how to shoot better. But a lot of it, I believe, is the desire to connect, to get the artwork out of the realm of the personal and into some kind of forum where it is connecting. It is so interesting to note how keyed up, excited, nervous, just plain alive people are in the moment when a room puts its undivided attention on their work.

2. It is strange to be positioned as an authority. This was a situation where I was one of two, sometimes three, people in the room designated to offer comments. At times I felt much more qualified as a kind of articulate audience member than as a person especially knowledgeable about photography. In a way it was freeing to be set up as an authority, kind of like putting on a mask.

3. In some ways, it is much easier to be asked to comment as an authority figure than it is to take part in a feedback dialogue of multiple, equalized voices. It's easy to rattle off your reaction to something. What we ask responders to do in a CRP session actually requires a level of listening, thinking, processesing, weighing, choosing to speak or keep silent, that is highly demanding for those who really invest in it.

4. Questions are really powerful. I felt as a commentator that I had the most chance of being useful when the photographers brought not only their images but their questions to the table. And I had the most chance of getting through to something valuable for the artists when I was able to form a good question for them to think about. But we knew that, didn't we?

5. Editing is artistry. Photography is an artform that puts this principle in high relief. What you create is just the beginning. How you choose from what you create is where voice and meaning truly emerge.

1. People really want the feedback experience. We had high participation in this event, much of it from folks who'd never been to Photoworks before. It seems that if you just hang out the shingle and say you are offering critique, folks will show up. Why? Some of it is a desire for guidance, since most of the photographers were asking for advice about organization or how to shoot better. But a lot of it, I believe, is the desire to connect, to get the artwork out of the realm of the personal and into some kind of forum where it is connecting. It is so interesting to note how keyed up, excited, nervous, just plain alive people are in the moment when a room puts its undivided attention on their work.

2. It is strange to be positioned as an authority. This was a situation where I was one of two, sometimes three, people in the room designated to offer comments. At times I felt much more qualified as a kind of articulate audience member than as a person especially knowledgeable about photography. In a way it was freeing to be set up as an authority, kind of like putting on a mask.

3. In some ways, it is much easier to be asked to comment as an authority figure than it is to take part in a feedback dialogue of multiple, equalized voices. It's easy to rattle off your reaction to something. What we ask responders to do in a CRP session actually requires a level of listening, thinking, processesing, weighing, choosing to speak or keep silent, that is highly demanding for those who really invest in it.

4. Questions are really powerful. I felt as a commentator that I had the most chance of being useful when the photographers brought not only their images but their questions to the table. And I had the most chance of getting through to something valuable for the artists when I was able to form a good question for them to think about. But we knew that, didn't we?

5. Editing is artistry. Photography is an artform that puts this principle in high relief. What you create is just the beginning. How you choose from what you create is where voice and meaning truly emerge.

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Stop the Misery!

Sometimes you just have to go negative in order to make a point. That was my reaction upon reading “How To Feel Miserable as an Artist,” a ten point list that is currently going viral in the arts world. It arrived at my desktop courtesy of Dance Exchange artist Ben Wegman, and I’ve traced it to the blog of artist/author Keri Smith – someone who is new to me, but whose work I definitely plan to check out in greater depth.

Looking over this list I’m struck by how many of these sources of artistic misery stem from two questions: How do we measure success? and What constitutes approval?: Ultimately, while acknowledging all the external forces (family, money, clients, society) that bear on an artist’s sense of self-worth, Keri Smith is clearly preaching that artists need to look within for the final measure of their own value.

What does this mean for critique? Maybe that it’s overvalued. Maybe that artists need to strengthen their own internal voices within the dialogue of criticism. Maybe that we can take nothing for granted in terms of how we measure quality.

Looking over this list I’m struck by how many of these sources of artistic misery stem from two questions: How do we measure success? and What constitutes approval?: Ultimately, while acknowledging all the external forces (family, money, clients, society) that bear on an artist’s sense of self-worth, Keri Smith is clearly preaching that artists need to look within for the final measure of their own value.

What does this mean for critique? Maybe that it’s overvalued. Maybe that artists need to strengthen their own internal voices within the dialogue of criticism. Maybe that we can take nothing for granted in terms of how we measure quality.

Friday, November 14, 2008

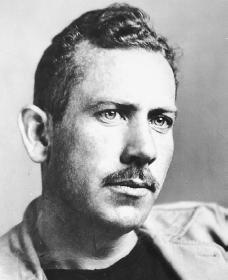

Notable Quotable: John Steinbeck

A guy at my gym this morning was wearing a T-shirt that read:

Can we manage that desire? Can we channel it constructively? Should we just get over it?

The theory of the Critical Response Process on this issue might be: Step One provides the corroboration that something, at least, is working, something is conveying and communicating. Having that impulse fed, even to a limited degree, helps open us up to hearing more -- even advice.

"No one wants advice -- only corroboration."I wonder if Steinbeck was thinking of creative matters. It certainly holds a grain of truth when applied to artistic works-in-progress. When we put such work forward for comment, there’s often a part of us that wants most just to get confirmation that what we’ve done is brilliant and doesn’t need any fixing.

--John Steinbeck

Can we manage that desire? Can we channel it constructively? Should we just get over it?

The theory of the Critical Response Process on this issue might be: Step One provides the corroboration that something, at least, is working, something is conveying and communicating. Having that impulse fed, even to a limited degree, helps open us up to hearing more -- even advice.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Well, Yes and No...

Here’s another reflection about Critical Response Process emerging from our recent work in Boulder, as passed on from an artist in that community by ATLAS’s Rebekah West:

Yes. Once you’ve learned the Critical Response Process, you may well find such concepts as the Step One comment, the neutral question, and the permissioned opinion to be very useful on their own. They can be effective when used with colleagues who are versed in CRP and who grasp the bigger context, but they also can be applied “stealth style” with people who may have no idea where you are coming from. (Using Step Ones in particular – naming meaningful details and citing stimulating connections – may lead you conversation partner to decide that you are very intelligent!) And once people get their legs in CRP, it’s possible to jump from a step one to a step four in a quick exchange. But beware – and this is the caveat on the “Yes” answer -- when the Process is thus “sampled” you may have useful tools for a feedback conversation, but you don’t have a full-fledged critique process. Every now and then you need one.

No. The elements of the Process have been refined over time and sequenced for a reason. Mess with it at your peril. Now, maybe there’s been some cherry picking of CRP somewhere that has effectively combined it will other elements, but I haven’t seen it. I have seen some train wrecks, though, when folks have played fast and loose with the Process.

My final advice? Do the Process in its full form a bunch of times. Get to know it well. Stay curious even as you encounter challenges with it. Don’t try adaptations or extrapolations until you feel secure with CRP in it four-step format.

(some artists) argue people use "parts of it." My thought is that you either use the whole "container" or you do not use it. Using convenient "parts" does not get it done!!!!This comment raises a stimulating question: Can you use just parts of the Critical Response Process and still have an effective feedback experience? I’ll offer the Yes answer and the No answer:

Yes. Once you’ve learned the Critical Response Process, you may well find such concepts as the Step One comment, the neutral question, and the permissioned opinion to be very useful on their own. They can be effective when used with colleagues who are versed in CRP and who grasp the bigger context, but they also can be applied “stealth style” with people who may have no idea where you are coming from. (Using Step Ones in particular – naming meaningful details and citing stimulating connections – may lead you conversation partner to decide that you are very intelligent!) And once people get their legs in CRP, it’s possible to jump from a step one to a step four in a quick exchange. But beware – and this is the caveat on the “Yes” answer -- when the Process is thus “sampled” you may have useful tools for a feedback conversation, but you don’t have a full-fledged critique process. Every now and then you need one.

No. The elements of the Process have been refined over time and sequenced for a reason. Mess with it at your peril. Now, maybe there’s been some cherry picking of CRP somewhere that has effectively combined it will other elements, but I haven’t seen it. I have seen some train wrecks, though, when folks have played fast and loose with the Process.

My final advice? Do the Process in its full form a bunch of times. Get to know it well. Stay curious even as you encounter challenges with it. Don’t try adaptations or extrapolations until you feel secure with CRP in it four-step format.

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Quack!

Speaking of variations on the Critical Response Process, I heard about the following mode of critique being used in a college level drama class. After a showing, the instructor poses three questions:

“Isn’t that just like the Critical Response Process?” I was asked.

Well, no.

But I can see the resemblance. In common with CRP is the value placed on inquiry and observation, and the good will implied by that big-hearted “Waddaya love?” But in the nuance between this and Critical Response lie some major differences. CRP’s opening round, which is initiated by the facilitator’s question “What was exciting, stimulating, meaningful, memorable?” offers both more focus than “What did you see?” and more range of possibility than “What did you love?” -- and does so in one question rather than two. The responder isn’t required to love anything, and the process isn’t premised in the idea that the artist needs to be loved. Big difference.

What about “What are your questions?” It’s always good to ask for questions. And it’s even better to ask for neutral questions (CRP Step 3) because the discipline of framing neutrally helps the questioner and opens up the dialogue with the artist.

What quacks like a duck may not swim like a duck.

And in that case, it’s not a duck.

What do you see?

What do you love?

What are your questions?

“Isn’t that just like the Critical Response Process?” I was asked.

Well, no.

But I can see the resemblance. In common with CRP is the value placed on inquiry and observation, and the good will implied by that big-hearted “Waddaya love?” But in the nuance between this and Critical Response lie some major differences. CRP’s opening round, which is initiated by the facilitator’s question “What was exciting, stimulating, meaningful, memorable?” offers both more focus than “What did you see?” and more range of possibility than “What did you love?” -- and does so in one question rather than two. The responder isn’t required to love anything, and the process isn’t premised in the idea that the artist needs to be loved. Big difference.

What about “What are your questions?” It’s always good to ask for questions. And it’s even better to ask for neutral questions (CRP Step 3) because the discipline of framing neutrally helps the questioner and opens up the dialogue with the artist.

What quacks like a duck may not swim like a duck.

And in that case, it’s not a duck.

Monday, November 10, 2008

Pervasive Process?

“I don’t think the Dance Exchange folks realize how pervasive the Critical Response Process is. Every artist in the United States who has any form of critical response is using a derivative of the CRP.”

A comment to that general effect was passed on to us by Rebekah West, who recently hosted a small Dance Exchange team for Critical Response activities at the ATLAS Alliance at the University of Colorado, Boulder. In her email reporting this comment, she asked what I thought.

Here goes: I’m a little skeptical given the absolute quality of the comment. But Critical Response Process definitely has a life of its own out there beyond the institution where it began. It is in the nature of a technique like CRP that it may get passed hand-to-hand, or mouth-to-ear, on a kind of oral history basis. Hence derivatives are inevitable. Some of them are probably thoughtful adaptations for the needs of a particular setting and use; some may turn out looking like more distant relatives (I’ll admit I’m resisting the urge to use the work “bastardizations”); and sometimes worthy practices may have features in common with CRP but descend from separate lineages.

I definitely hear reports of CRP thriving in places where we had no idea that it was being used. I also encounter plenty of people in the arts field for whom it is entirely new and surprisingly different from what they are used to. And then I hear people describe what they think is CRP or “just like your process,” when in fact what they are describing is different in one or more essential features.

Frankly, it is a challenge for Dance Exchange as an institution to keep track of where the Critical Response Process gets used, who’s doing it, how it gets varied, what’s a practice we’d endorse and what isn’t. We have ongoing discussions in our offices about getting an intern to do research on CRP’s use in the field and about the desirability/feasibility of setting up a certification program. The most realistic position for us at this point is to do our best to be a resource with our book, trainings, and now this blog; and to continue to act as a kind of laboratory probing deeper and wider into the applications and implications of a process that's clearly too big to be contained by just the institution that started it.

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

This Is Also a Form of Critical Response...

Sunday, November 2, 2008

Genial Taskmaster

Today's New York Times includes an article on Donald Palumbo, who recently took the reins as chorus master at the Metropolitan Opera. Thinking about the topic of artistic leadership styles (addressed in my "screaming and throwing chairs" post last week), I was struck by the following passage, which quotes Mr. Palumbo as he gives notes to the chorus preparing for the Met's new production of Berlioz's Damnation of Faust:

"“No, your ‘hélas’ must not sound like whining,” Mr. Palumbo urged. “The color is too bright and high. ... Articulate with more pulse. ... Trust your instincts, and go with it when the harmonies weave together. ... Basses, on that ‘tra-la-ho-ho’ passage, give me more boom and a less churchlike ‘ho.’... Can that phrase bloom rather than just explode? ... Grab every note of this rising passage. Don’t just run up the scale. ... The chorus of celestial spirits must be completely passive, with no forward pressure on the voice at all. Soft but specific. Don’t ooze into the note.”

The specificity of this language is just bracing, and I think it's notable that in every case where he cites a "don't" Palumbo also gives a very directive "do." No screaming or throwing chairs. The article notes the marked improvement in the work of the Met chorus since this "genial taskmaster" assumed his post.

"“No, your ‘hélas’ must not sound like whining,” Mr. Palumbo urged. “The color is too bright and high. ... Articulate with more pulse. ... Trust your instincts, and go with it when the harmonies weave together. ... Basses, on that ‘tra-la-ho-ho’ passage, give me more boom and a less churchlike ‘ho.’... Can that phrase bloom rather than just explode? ... Grab every note of this rising passage. Don’t just run up the scale. ... The chorus of celestial spirits must be completely passive, with no forward pressure on the voice at all. Soft but specific. Don’t ooze into the note.”

The specificity of this language is just bracing, and I think it's notable that in every case where he cites a "don't" Palumbo also gives a very directive "do." No screaming or throwing chairs. The article notes the marked improvement in the work of the Met chorus since this "genial taskmaster" assumed his post.

Friday, October 31, 2008

Switching Hats

The Critical Response hat isn’t the only hat I wear. And sometimes when I’m wearing one of those other hats, I can’t get into the Critical Response hat quite as fast as I’d like to.

The Critical Response hat isn’t the only hat I wear. And sometimes when I’m wearing one of those other hats, I can’t get into the Critical Response hat quite as fast as I’d like to.Case in point: this past Sunday I was at the photography education center where I’m active, Photoworks Glen Echo. I was leading the workshop that I teach once or twice a year, focused on the craft of combining words and pictures. I guess you could say I was wearing my teaching hat as opposed to my facilitating hat, my aesthetics hat as opposed to my critique hat, my Photoworks hat as opposed to my Dance Exchange hat. Not that any of those terms are mutually exclusive, but -- contrary to popular rumor -- my head is only just so big.

There comes a point in most photography classes when a student will spread prints out on the table, or post them on a board for viewing. People who frequent photo workshops are conditioned to treat this as critique time. And once it’s critique time, if the teacher doesn’t firmly establish a format from the outset, the conversation can pretty much slide anywhere. Which is what happened when one of the workshop participants laid out a series of portraits for a book she is planning.

Now, it wasn’t a disaster by any means. The artist was accomplished, so there was plenty of admiration for both the technical quality and the substance of her work. She had already stated her challenges and options for adding words to the images during the workshop’s opening round of introductions. But as soon as she put down a page of text next to one of the photos to show us how a spread in her book might appear, the fix-its started flying. “Make the text shorter.” “Use this sentence here, this is the essence.” “Put the interviews in the back of the book.” “You could try making some of the text larger, like a call-out in a magazine.” (Full disclosure: some of those fix-its came from me, since by that point jumping into the melee seemed the best way to offer my guidance.)

Lots of stuff starts going on in my own head in a moment like this. As a teacher, I wonder if I’m losing authority or if my opinion counts less because other people in the room have strong directives to offer. I’m trying to check the emotional temperature of the artist whose work is on the table – is she taking this in or is she shutting down? I’m weighing the merits of such fix-its against the value of good questions or less directive statements, multiple options against the one-problem, one-solution model. Lastly, I’m looking at the clock, since we’re already behind on the schedule for the afternoon.

The Critical Response Process, of course, offers help in all of those challenges, except perhaps the time constraint. And time is probably the reason why I didn’t step back, put on the CRP hat and try to redirect the interaction.

I always say that I consider an event a success if I know how I’ll do it better next time. So next time, while not necessarily engaging in a full-blown Critical Response session, I’ll probably do the following:

--Get the artist to talk about her challenges when she shows her work as opposed to much earlier in the workshop.

--Mindfully mention as the prints are placed on the table that this marks a transition where we’re likely to move into critique mode, and set some guidelines

--Encourage people to take a step back from the fixit: Can they frame the principle behind the suggestion they want to make rather than telling the artist what to do differently? Then I'd try to follow that principle myself.

As Liz often says, our impulse to fix another artist’s work can be a highly creative one. Channeling that impulse for the benefit of both people in the dialogue is the challenge. More on that topic soon, I hope.

It’s 5:30 in the evening, so please excuse me while I change into my Halloween hat.

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Blog Bounce from Boulder

Artist/filmmaker Laura Tyler was on hand eariler this month in beautiful Boulder, when Liz Lerman -- along with Dance Exchange Production Manager Amelia Cox and me -- made some presentations at the ATLAS Alliance of the University of Colorado. Our little team was there to talk about quality, collaboration, the art/technology connection, and, naturally, Critical Response. Laura filed her incisive impressions on her own blog, so check it out.

I am particularly stimulated by what Laura says about the relationship of self-assessment to the passage of time. Fit fodder for future reflection!

I am particularly stimulated by what Laura says about the relationship of self-assessment to the passage of time. Fit fodder for future reflection!

Monday, October 27, 2008

The Screaming-and-Throwing-Chairs School of Choreography

I always enjoy the "Advice for Dancers" column in Dance Magazine. Reading about the problems of artists in the ballet and show biz sectors offers an interesting window on life beyond the Dance Exchange's sometimes contrarian corner of the dance world. In the just-released November edition, a reader asks: "My friend is working for a Tony Award-winning choreographer who screams and throws chairs -- isn't it illegal to treat company members this way?"

This reminded me of a story I recently heard about a now-deceased big-name choreographer. "Treat your dancers like s***," he advised a younger colleague (my informant, actually). "That way you'll always get what you want from them."

Sad.

Putting the two stories together did make me wonder: Is there a school of thought in the dance world that holds that fear, intimidation, and abuse are effective means for getting good performances from dancers? Is it just temperament that accounts for the screaming-and-throwing-chairs approach to dancemaking, or is it a kind of learned (and taught) behavior? And when choreography is imparted as a discipline, how often are the relational, communicative aspects of the dancer-choreographer dynamic included in the curriculum?

Since my education in dance is pretty much limited to Dance Exchange, I can't answer these questions in reference to dance-at-large. But I suspect that choreographic technique rarely encompasses how to relate to your dancers, and choreographers end up emulating whatever behaviors -- good, bad, or indifferent -- were perpetrated on them when they were dancers.

I'd like to believe that whether a choreographer favors a nurturing or a tough-minded approach, respect is always a basic value in how artists are treated. And I can't help but wonder if more could be done to teach good communication and leadership to emerging dancemakers.

This reminded me of a story I recently heard about a now-deceased big-name choreographer. "Treat your dancers like s***," he advised a younger colleague (my informant, actually). "That way you'll always get what you want from them."

Sad.

Putting the two stories together did make me wonder: Is there a school of thought in the dance world that holds that fear, intimidation, and abuse are effective means for getting good performances from dancers? Is it just temperament that accounts for the screaming-and-throwing-chairs approach to dancemaking, or is it a kind of learned (and taught) behavior? And when choreography is imparted as a discipline, how often are the relational, communicative aspects of the dancer-choreographer dynamic included in the curriculum?

Since my education in dance is pretty much limited to Dance Exchange, I can't answer these questions in reference to dance-at-large. But I suspect that choreographic technique rarely encompasses how to relate to your dancers, and choreographers end up emulating whatever behaviors -- good, bad, or indifferent -- were perpetrated on them when they were dancers.

I'd like to believe that whether a choreographer favors a nurturing or a tough-minded approach, respect is always a basic value in how artists are treated. And I can't help but wonder if more could be done to teach good communication and leadership to emerging dancemakers.

Friday, October 24, 2008

Taking My Bias to the Opera

I went to the opera last month to see Bizet's The Pearl Fishers performed by the Washington National Opera. The sets and costumes in this much-travelled production were by Zandra Rhodes, the trendy-but-individualistic British fashion designer.

Looking back, I'm aware that I walked into the theater with two particular biases.

Bias No. 1, regarding the participation of Ms. Rhodes: Fashion designers don't necessarily make good theatrical costume designers. The two disciplines are very different, in fact, and it always seems like a bit of an insult to costume designers who have toiled in the backstage trenches when opera managments see fit to headline a star fashion designer with an assignment like this. (Some fuss was being made over Rhodes' involvement, with an insert in the program alerting us to the fact that her scarves and other accessories were on sale at the Kennedy Center gift shop.)

Bias No. 2: The score of The Pearl Fishers (an early work by the composer of the much more famous Carmen) has some beautiful passages. It also has some stretches of much less inspired music. My very biased adjectives for said music include banal, vapid, polite. I'll admit that this isn't a very original opinion.

It's interesting to walk into an artistic situation conscious of your bias. You could look to the situation to reinforce your opinion, or you could decide that your opinion might be subject to change based on what you encounter. I guess in this situation I did a bit of both.

Regarding my bias against fashion designers on the opera stage, I actually went somewhere. For this work -- set in "ancient Celon" -- I thought Zandra Rhodes' costumes created some gorgeous stage pictures with their wide pallette of deep, jewel-like colors. They struck a note of kitschy over-the-top exoticism that was just right for a work that trades in spectacle and a sort of touristy delight in foreign cultures. They didn't do a whole lot to advance your understanding of characters or relationships, but it's not like The Pearl Fishers is Ibsen. Conclusion: a fashion designer's sensibilty can work on the opera stage when there's a good match between that sensibility, the work in question, and the overall production concept.

As to my bias about the music of The Pearl Fishers , I remained pretty rock-steady in my very conventional opinion. But looking back, I'm aware that I didn't do much to challenge myself. What if I'd walked into the opera house saying, "I'm going to listen harder. I going to pay attention to the structure of the music or the orchestration. I'm going to cock my ears for something I haven't heard before." But I didn't and it's no suprise that my opinion didn't change.

I remember a sign on someone's dorm room door when I was in college:

"If you haven't changed your opinon about something in the last six months, check your pulse. You may be dead."

It's always worthwhile testing an opinon, but it does take willingness and an effort of mind.

Thursday, October 23, 2008

I Have an Opinion About That Opinion...

“You’re another pretty choreographer making pretty dances.”

A student artist we know recently heard those words from a faculty reviewer when her work was under consideration for a prestigeous opportunity. Well, not exactly those words. I’ve fictionalized the scenario a bit in the interest of protecting the innocent... and the guilty.

Imagine hearing that, though. The mind reels. Nothing damns art quite like “pretty,” and few things demean a person -- particularly a female person -- quite like being characterized by appearence alone. And the suggestion that one's work and one's self can be dismissed as part of a large class of similar mediocrities pretty much puts the bitter icing on this nasty slab of critical cake.

I can imagine only two reasonable responses, at least in the shortterm: retreat, as in yank down the shades, climb into bed and pull the sheets over your head for three days, or defensiveness. And -- repeat after me the wise words of Liz Lerman -- When defensiveness starts, learning stops.

That is the real shame of the instructor’s comment. In one condescending blow it ended the possibility of meaningful conversation with the student and the chance for anyone to do any learning. And this happened in an educational institution. Go figure.

Suppose -- and now I’m really fictionalizing because I’m postulating beyond anything I know about the actual situation -- suppose the teacher did have some concerns about limitations in the young artist’s aesthetic; suppose he (let’s assume it’s a he) observed the artist playing out self-image issues in ways that he believed were holding her work back; suppose he just likes edgier work; or suppose he thinks that socially conscious content trumps mere beauty (assuming that the two can’t coexist). Legitimate or not, all of those positions could be worthwhile starters to some kind of dialogue with the student, dialogue that might lead to insight, reflection, a fresh direction.

People often ask when the principles of CRP can be applied separate from the formal, four step process, and here’s a beautiful example of a situation where the neutral question (see CRP step 3) could be so helpful. Let’s try out a few:

--Tell me about your choice of subject matter.

--What is inspiring your work right now?

--Would you say that there’s a part of your personal story in this work? Tell me about that.

--How do you view your work in relation to that of your peers?

--How would you define your artistic concerns?

--How do you think about beauty?

And so on. The point is that they are conversation starters, not conversation stoppers, and that neutral quesions like these could lay the groundwork for trenchant opinion that the student might be ready to hear. Or a challenge for her to think about. Or some new curriculum ideas on the part of the professor (after all, if he's seeing so much "pretty" work from "pretty" students, doesn't he have the responsibility to change things?)

As it happened, the student artist seemed to be going into shut-down mode. She was actually scheduled for a Critical Response session on one of her works, but she bowed out on that opportunity, probably because she felt just too burned by the encounter of the day before. (Who could blame her?) And she was voicing some defensiveness too. I hope that defensiveness doesn't limit scope of her work in the future.

Whenever we say it, people reach for their pencils to write it down. So teachers, mentors, supervisors: cross-stitch this onto your pillowcases and sleep on it: When defensiveness starts, learning stops.

A student artist we know recently heard those words from a faculty reviewer when her work was under consideration for a prestigeous opportunity. Well, not exactly those words. I’ve fictionalized the scenario a bit in the interest of protecting the innocent... and the guilty.

Imagine hearing that, though. The mind reels. Nothing damns art quite like “pretty,” and few things demean a person -- particularly a female person -- quite like being characterized by appearence alone. And the suggestion that one's work and one's self can be dismissed as part of a large class of similar mediocrities pretty much puts the bitter icing on this nasty slab of critical cake.

I can imagine only two reasonable responses, at least in the shortterm: retreat, as in yank down the shades, climb into bed and pull the sheets over your head for three days, or defensiveness. And -- repeat after me the wise words of Liz Lerman -- When defensiveness starts, learning stops.

That is the real shame of the instructor’s comment. In one condescending blow it ended the possibility of meaningful conversation with the student and the chance for anyone to do any learning. And this happened in an educational institution. Go figure.

Suppose -- and now I’m really fictionalizing because I’m postulating beyond anything I know about the actual situation -- suppose the teacher did have some concerns about limitations in the young artist’s aesthetic; suppose he (let’s assume it’s a he) observed the artist playing out self-image issues in ways that he believed were holding her work back; suppose he just likes edgier work; or suppose he thinks that socially conscious content trumps mere beauty (assuming that the two can’t coexist). Legitimate or not, all of those positions could be worthwhile starters to some kind of dialogue with the student, dialogue that might lead to insight, reflection, a fresh direction.

People often ask when the principles of CRP can be applied separate from the formal, four step process, and here’s a beautiful example of a situation where the neutral question (see CRP step 3) could be so helpful. Let’s try out a few:

--Tell me about your choice of subject matter.

--What is inspiring your work right now?

--Would you say that there’s a part of your personal story in this work? Tell me about that.

--How do you view your work in relation to that of your peers?

--How would you define your artistic concerns?

--How do you think about beauty?

And so on. The point is that they are conversation starters, not conversation stoppers, and that neutral quesions like these could lay the groundwork for trenchant opinion that the student might be ready to hear. Or a challenge for her to think about. Or some new curriculum ideas on the part of the professor (after all, if he's seeing so much "pretty" work from "pretty" students, doesn't he have the responsibility to change things?)

As it happened, the student artist seemed to be going into shut-down mode. She was actually scheduled for a Critical Response session on one of her works, but she bowed out on that opportunity, probably because she felt just too burned by the encounter of the day before. (Who could blame her?) And she was voicing some defensiveness too. I hope that defensiveness doesn't limit scope of her work in the future.

Whenever we say it, people reach for their pencils to write it down. So teachers, mentors, supervisors: cross-stitch this onto your pillowcases and sleep on it: When defensiveness starts, learning stops.

Four Steps Toward Leadership

We're currently in conversation with a leading visual art school about doing a day of Critical Response work with their freshmen. Our contact there asked us to explain how CRP would help the students to build leadership skills. Here's part of my response -- with a bit of bold type for added emphasis:

'Nuff said ... for now.

If we are preparing young people to take positions in the world as artists and to get the most out of a higher education experience in artistic practice, it seems to me that we want to prepare them for a variety of functions: to be articulate in representing their own work; to collaborate effectively with fellow artists, clients, curators and commissioners; to both lead projects and to be an effective team member; and to teach.

Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process enhances leadership and collaborative capacities by enabling us to recognize and manage bias; by helping us be more articulate about our own work and that of others; by enhancing and constructively channeling our capacity for self-criticism; by sharpening listening skills and assuring that others will listen to us; and by imparting solid, easily grasped techniques for effective communication.

'Nuff said ... for now.

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

Notable Quotable: Jackson Pollock

A few years ago when Liz Lerman and I assembled our book on the Critical Response Process, I had fun collecting a series of quotes about critique, opinion, dialogue, and the purposes of art. In conjunction with some of my recent CRP teaching gigs, I've been making new additions to this collection.

A few years ago when Liz Lerman and I assembled our book on the Critical Response Process, I had fun collecting a series of quotes about critique, opinion, dialogue, and the purposes of art. In conjunction with some of my recent CRP teaching gigs, I've been making new additions to this collection.So (speaking of someone I mentioned in my last post) here's one I particularly like from abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock:

"There was a reviewer a while back who wrote that my pictures didn't have any beginning or any end. He didn't mean it as a compliment, but it was."

Ha! At the risk of stating the obvious, Pollock's reflection speaks to how the vision of an artist can sometimes transcend the limits of criticism. It shows that -- just like art -- an opinion can have a separate life and impact from that intended by its originator. And it suggests that when art makes a foray into new realms of expression and technique, terms of critique often lag behind.

Labels:

critique,

Jackson Pollock,

opinion,

quotations

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

I'll Be the Judge of That

From time to time, I'll hear an earnest soul praise the Critical Response Process as a "nonjudgmental" way to give feedback.

This always gets my hackles up, for reasons I'll explain in a minute ... but I suppose I should try to pose a neutral question in response to this kind of declaration. Something like: "'Nonjudgmental' is an interesting word. Can you say more about that? Tell me what you mean."

I'm going to guess that what they mean is that the artist getting the feedback does not feel personally judged as an individual, or that some standard remote from the artist's own intentions is not being used to measure a work-in-progress. And those two points are generally true enough: The Critical Response Process offers some great ways to keep the focus on the specific work in question and to engage artists themselves in setting some of the terms for how their work is reviewed.

But "nonjudgmental" as a blanket characterization of the Process is troublesome to me. May I rant for a second?

When did the idea of judging get a bad rap? At what point in our politically-correct, psychobabbling, I'm-okay-you're-okay epoch did it become a bad thing to be making judgments? So in response to the "nonjudgmental" label, I'd like to say: On the contrary. As we use CRP we will be making some judgments. An artist bringing work forward for discussion using the Process should be ready for some judgments about that work -- from others and from themselves. Moreover, judgment is a natural component of the artmaking process. Artists are constantly making choices, weighing options, saying "This isn't working, let's try that." Even what appear to be the most impulsive, intuitive, improvisational, "inspired" artistic gestures involve judgment. (Imagine Ella Fitzgerald scatting on "How High the Moon" or Jackson Pollock in his action-dance across the canvas.) It's simply judgment that is so ingrained, so integrated that it doesn't appear to entail the deliberation that we associate with the idea of judging.

It's all judgment and -- forgive me for my own spasm of earnestness -- it's all good.

What is perhaps distinctive about the Critical Response Process is that it isn't just the artist's work that is subject to judgment. Opinions offered in response to art also come under scrutiny, and those who react strongly are required to subject their opinions to a process of judgment: turning them into neutral questions, weighing their value in relation to the artist's response, and deferring to the artist's say as to whether those opinions may be expressed or not. There's even the possibility that an opinion might change in the course of the Process.

Everyone involved in a session of CRP might be subject to some judgment. Everyone, let's hope, will do some judging of their own thoughts, actions, and products. Everyone gets a chance to learn and change. How exciting!

This always gets my hackles up, for reasons I'll explain in a minute ... but I suppose I should try to pose a neutral question in response to this kind of declaration. Something like: "'Nonjudgmental' is an interesting word. Can you say more about that? Tell me what you mean."

I'm going to guess that what they mean is that the artist getting the feedback does not feel personally judged as an individual, or that some standard remote from the artist's own intentions is not being used to measure a work-in-progress. And those two points are generally true enough: The Critical Response Process offers some great ways to keep the focus on the specific work in question and to engage artists themselves in setting some of the terms for how their work is reviewed.

But "nonjudgmental" as a blanket characterization of the Process is troublesome to me. May I rant for a second?

When did the idea of judging get a bad rap? At what point in our politically-correct, psychobabbling, I'm-okay-you're-okay epoch did it become a bad thing to be making judgments? So in response to the "nonjudgmental" label, I'd like to say: On the contrary. As we use CRP we will be making some judgments. An artist bringing work forward for discussion using the Process should be ready for some judgments about that work -- from others and from themselves. Moreover, judgment is a natural component of the artmaking process. Artists are constantly making choices, weighing options, saying "This isn't working, let's try that." Even what appear to be the most impulsive, intuitive, improvisational, "inspired" artistic gestures involve judgment. (Imagine Ella Fitzgerald scatting on "How High the Moon" or Jackson Pollock in his action-dance across the canvas.) It's simply judgment that is so ingrained, so integrated that it doesn't appear to entail the deliberation that we associate with the idea of judging.

It's all judgment and -- forgive me for my own spasm of earnestness -- it's all good.

What is perhaps distinctive about the Critical Response Process is that it isn't just the artist's work that is subject to judgment. Opinions offered in response to art also come under scrutiny, and those who react strongly are required to subject their opinions to a process of judgment: turning them into neutral questions, weighing their value in relation to the artist's response, and deferring to the artist's say as to whether those opinions may be expressed or not. There's even the possibility that an opinion might change in the course of the Process.

Everyone involved in a session of CRP might be subject to some judgment. Everyone, let's hope, will do some judging of their own thoughts, actions, and products. Everyone gets a chance to learn and change. How exciting!

Monday, October 20, 2008

In the Bathtub with Andrew Sullivan

I was in the tub last night reading an article in The Atlantic by columnist/pundit Andrew Sullivan. His subject was blogging, and the piece was resonant with Sullivan's enthusiasm for this burgeoning mode of communication. For me his thesis was best summed up in the passage where he likens traditional journalism to scored classical music, blogging to improvised jazz. I rose from my bath with my dormant curiosity about the form re-stimulated. I'm ready to give it a try. (I wonder how many other new blogs that article will spawn?)

My subject is critique, and the intended centerpiece for this new-born blog is Liz Lerman's Critical Response Process. In my capacity as Humanities Director for Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, I have been actively involved for almost ten years in training, facilitating, and writing about this four-step process that helps artists get functional feedback on work-in-progress by harnessing the power of dialogue and inquiry. Fresh from a trip to the ATLAS Institute at the University of Colorado in Boulder where Liz and I led training and discussion in the Process, I'm convinced that there's a role for a forum about this widely-embraced mode for critical dialogue.

So here goes.

My subject is critique, and the intended centerpiece for this new-born blog is Liz Lerman's Critical Response Process. In my capacity as Humanities Director for Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, I have been actively involved for almost ten years in training, facilitating, and writing about this four-step process that helps artists get functional feedback on work-in-progress by harnessing the power of dialogue and inquiry. Fresh from a trip to the ATLAS Institute at the University of Colorado in Boulder where Liz and I led training and discussion in the Process, I'm convinced that there's a role for a forum about this widely-embraced mode for critical dialogue.

So here goes.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)